“Welcome to Country” has become a ubiquitous and tiresome aspect of Australian life. Before every meeting, assembly, and football game, you—as an outsider—must be welcomed.

Most of us are like Atheists in Church during these ceremonies. We think they’re retarded, but we don’t say anything, because we don’t want to be construed as racist (or worse still, someone who watches Sky News). So we grit our teeth and say the prayer, “We, the employees of Hungry Jacks, would like to acknowledge that we are meeting on the stolen lands of the Warrananggurrimbarrawirra people…”

On April 25, 2025, a ceremony commemorating the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzacs) was held in Melbourne. As the veterans were being "Welcomed to Country", someone yelled, "It's our country… We don't have to be welcomed."

But whose country is it?

If you asked the men of Gallipoli, Tobruk, El Alamein, and Kokoda, they would have answered: the white man's. The modern Australian recoils at such an answer. In fact, they'd probably denounce it as un-Australian. And yet, that is invariably what the Anzacs thought. And that is invariably why they fought. They fought to defend their country, because it was theirs. Welcome to Country ceremonies imply that white Australians are guests being graciously received on land that is not theirs. And that is why people in the audience booed.

This essay explores the rise and fall of Australian nationalism. It will outline how Australia transformed from a hodgepodge of British colonies into a unified nation; how this nation produced a unique “southern breed” of the Anglo-Saxon race that fought gallantly in the First World War; how those soldiers became the cornerstone of our national mythology; and how that mythology is being subverted by leftists.

Yellow Peril

In the 19th century, Christianity began waning across the Western world. The vacuum was filled by nationalism, a secular religion that enabled Europeans to maintain social cohesion in the absence of actual religion. Like Christianity, nationalism answered one of life’s most fundamental questions: Who am I?

You are a Swede, Frenchman, or (God forbid) Bulgarian.

Before converting to the secular religion of Nationalism, Australia was a hodgepodge of colonies. Each colony had its own laws, its own flag, and even its own military. A man from Sydney felt no particular loyalty to a man from Perth or Adelaide. But this began to change in the second half of the 19th century.

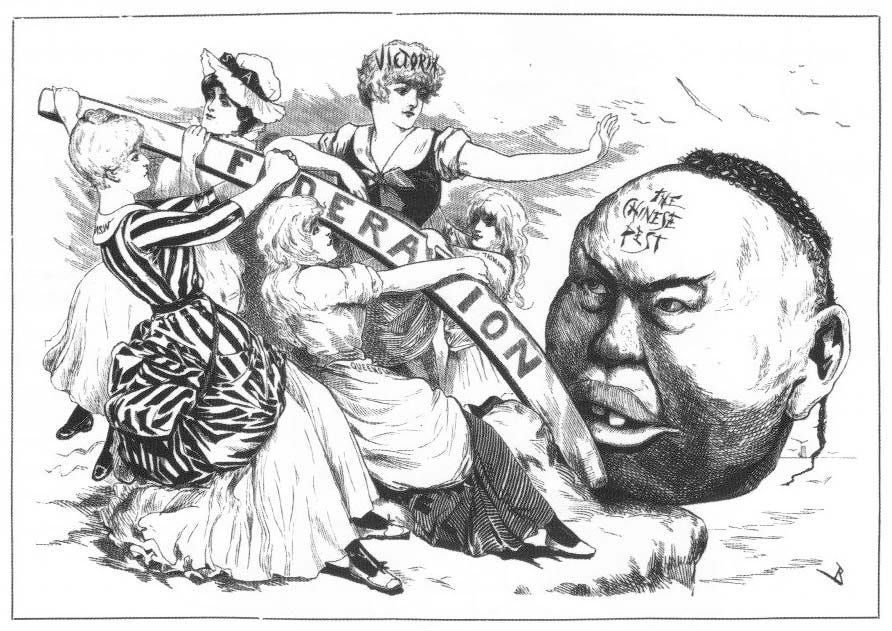

Nationalist sentiment emerged in response to migration, particularly from Asia. Chinese miners began arriving in Victoria in the 1850s, and by 1854, there were 2,000 of them on the goldfields. For the Victorians, that was 2,000 too many. The colonial government restricted immigration from Asia. But the Chinese circumvented Victoria’s restrictions by sailing to South Australia, which had different immigration laws. From there, they travelled by foot across Victoria’s unguarded border. By 1858, one quarter of Victoria’s miners were Chinese. In Victoria's Buckland Valley, Chinese miners outnumbered Europeans three to one.

This was not unique to Victoria. In New South Wales, Chinese miners outnumbered Europeans three to one. In the tin mines of North East Tasmania, Europeans were outnumbered 10 to one. Along the Palmer River in Queensland, over 90% of the miners were Chinese.

Similar trends could be observed in Far North Queensland. Plantation owners used Melanesian labor to harvest sugar. At the peak of the plantation era, almost half the people in the sugar towns were Pacific Islanders.

Many feared that the goldfields and sugar towns were a preview of Australia's future. This fear led colonial governments to restrict or outright ban migration from non-European countries.

In 1885, the Brisbane parliament informed the sugar barons that the importation of labor from the Pacific would be banned. This sparked a secessionist movement. A petition with over 10,000 signatures was sent from North Queensland to Queen Victoria, asking for a separate colony. This seventh colony would be a stronghold of colored labor.

Many worried that an independent North Queensland would flood the country with slave labor, and permanently change the demographics of the country. This fear was expressed by the Cooktown Courier:

We [the Cooktown Courier] have no hesitation in saying that a self-governing colony formed in the far North of Queensland, and cut off from all control by the South, would form itself probably in less than a generation into a community resembling those of Georgia, South Carolina, and the Slave States before the Civil War in America. It would become the plague spot of Australia.

The North Queensland secessionist movement failed, but it revealed a fundamental flaw in Australia's colonial structure. A single colony with a lenient immigration policy could undermine the border security of all its neighbors. Foreigners could easily enter through one colony to access another, just as Chinese migrants had used South Australia to enter Victoria.

To effectively control immigration, the colonies needed a unified policy—which required a unified nation. This occurred on the 1st of January, 1901.

The raison d'être behind Australian unification was controlling immigration. This point was made explicitly by Alfred Deakin, Australia's second prime minister, “no motive operated more powerfully in dissolving the political divisions which previously separated us, than the desire that we should be one people and remain one people without the mixture of races.”

The first Act passed by the new federal parliament was the Immigration Restriction Act, more commonly known as the White Australia Policy. It effectively barred non-white immigration.

Dysgenics Down Under

Opposition to immigration inspired the white settlers to convert to the secular religion of nationalism. But Australian nationalism lacked a central tenet of the faith: a glorious foundation myth. America had the Puritans. Rome had Romulus and Remus. Australia had Archibald Nifflebottom, the chimney sweep who got caught sniffing Lady Penelope's panties.

Australia began as a dumping ground for the dregs of British society. Our founding stock were pickpockets, prostitutes, and petty criminals. Today, many Australians believe that the convicts were political prisoners, rick-burners, trade-unionists, and the like. This is an ennobling delusion. The vast majority were simply thieves. About four-fifths of all transportation was for offences against property.

This created an insurmountable problem for Australian nationalists. They needed a founding myth, but they couldn't celebrate their nation's founding. They needed to think of themselves as a “chosen people”, but the only thing they had been chosen for was exile.

Australia's convict heritage also fueled anxieties about “corrupted blood.” Many viewed native born Australians as “the children of convicts,” heirs of a depraved gene pool, who would inherit their ancestors' criminal tendencies. The New South Wales judge, Alfred Stephen, said that "crime descends, as surely as physical properties and individual temperament." Some even believed that criminality was stamped onto the Australian face. Whilst travelling around Australia, Anthony Trollope claims to have seen "the Bill Sikes physiognomy" everywhere.

Australia was a nation of stock-breeders, who meticulously tracked lineages and pedigrees. They witnessed firsthand how characteristics passed from one generation to the next. This ingrained a rigid understanding of genetic inheritance in the Australian psyche. If traits were passed down as reliably in humans as they were in livestock, then what did this mean for a people descended from convicts? Was an Australian simply an Englishman of bad stock? Such thinking left little room for national pride.

Ashamed of their penal origins, Australian nationalists turned to the mythos of the frontier.

The Frontier Thesis

In 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner wrote "The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” This essay argued that the frontier made Americans, and America, what they were. The experience of claiming and taming wild nature made for a vigorous, often violent people, that were distinct from their European counterparts. To quote Turner:

The wilderness masters the colonist. It finds him a European in dress, industries, tools, modes of travel, and thought. It takes him from the railroad car and puts him in the birch canoe. It strips off the garments of civilization and arrays him in the hunting shirt and the moccasin. It puts him in the log cabin of the Cherokee and Iroquois. He shouts the war cry and takes the scalp in orthodox Indian fashion. In short, the frontier environment is too strong for the man. He must accept the conditions which it furnishes or perish, and so he fits himself into the Indian clearings and follows the Indian trails. Little by little he transforms the wilderness, but the outcome is not the old Europe… Here is a new product that is American.

Australia, like America, is a large land which was settled by Europeans who pushed the frontier of settlement westward from the eastern seaboard, over the mountains, and across the plains beyond. It was inevitable, then, that Australians would be attracted to the frontier thesis, and seek to apply it to themselves.

The Australian, like the American, had been shaped by his experiences with wild nature. He had battled with bush, droughts, and fire. “All this fighting with men and with nature, fierce as any warfare”, the historian C.E.W Bean observed, “has made of the Australian as fine a fighting man as exists.”

Bean believed that the battle against the bush had resulted in a unique “Southern breed” of the Anglo-Saxon race. This “Southern breed” was bigger, stronger, and more fiercely independent than its European counterpart. The bush-fashioned Australian was, he wrote, “the Briton re-born, as it were—a Briton with the stamina and freshness of the 16th century living amongst the material advantages of the twentieth century.”

The Australian hadn't descended from criminality; he had ascended through conquest of nature.

The Anzac Legend

In the First World War, Australians fought to defend the British Empire. But they also fought to defend white Australia. This point was made explicitly by Australia’s Prime Minister, Billy Hughes. At a large rally in Sydney, he said: “If Britain wins and we stand with her, the White Australia policy is forever safe.” He finished this speech by imploring all eligible men to "fight for white Australia."

Australia and New Zealand had never gone to war before. As a result, there weren’t many experienced soldiers among the Anzacs. These young men—representing two young nations—were heading into battle for the first time. This lent the Gallipoli Campaign enormous symbolic significance. It was seen as the first true test of Antipodean manhood.

The Gallipoli Campaign was the brainchild of Winston Churchill. He believed that the stalemate on the Western front could be broken by attacking Germany's Ally, the Ottoman Empire. The Allies would land on the Gallipoli Peninsula, secure the Dardanelles strait, then attack Constantinople. Needless to say, things didn’t unfold quite so neatly.

On the 15th of April, 1915, the Anzacs arrived at Gallipoli. The English war correspondent, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, was impressed by what he saw:

I do not suppose that any country in its palmiest days ever sent forth to the field of battle a finer body of men than these Australian, New Zealand and Tasmanian troops. Physically they are the finest men I have ever seen in any part of the world. In fact, I had no idea such a race of giants existed in the twentieth century. Some of their battalions average 5' 10" and every man seems to be a trained athlete.

John Masefield, the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, was similarly struck by the Anzacs’ appearance:

the finest body of young men ever brought together in modern times. For physical beauty and nobility of bearing they surpassed any men I have ever seen; they walked and looked like kings in old poems, and reminded me of the line in Shakespeare: “Baited like eagles lately bathed.”

The English soldier, by comparison, was found lacking. C.E.W Bean, who documented the Gallipoli campaign as Australia's official war correspondent, made the following entry in his diary:

The truth is that after 100 years of breeding in the slums, the British race is not the same, and can’t be expected to be the same, as in the days of Waterloo. It is breeding one fine class at the expense of all the rest. The only hope for it is that these puny, narrow-chested little men may, if they come out to Australia or New Zealand or Canada, within two generations breed men again. England herself, unless she does something heroic, cannot hope to.

The war correspondent and historian, Alan Moorehead, wrote something very similar:

A strange change had overtaken this transplanted British blood. Barely a hundred years before their ancestors had gone out to the other side of the world from the depressed areas of the United Kingdom, many of them dark, small, hungry men. Their sons who had now returned to fight in their country’s first foreign war had grown six inches in height, their faces were thin and leathery, their limbs immensely lithe and strong.

The physical differences between Australian and English soldiers seemed to confirm the frontier thesis. The Australian was not an Englishman of “bad stock”. He was a distinct breed of the Anglo-Saxon race; one that had been strengthened by the harsh environment of the Australian bush.

On the 25th April, 1915, the Anzacs stormed ashore the Peninsula. To quote Alan Moorehead again:

The men jumped out of the boats and began wading the last fifty yards to the land. A few were hit, a few were dragged down by the weight of their packs and drowned, but the rest stumbled through the water to the beach. A group of Turks was running down the shore towards them. Forming themselves into a rough line and raising their absurd cry of “Imshi Yallah” the Dominion soldiers fixed their bayonets and charged. Within a few minutes the enemy before them had dropped their rifles and fled. The Anzac legend had begun.

Ghastly months of slaughter followed. The Turks defended their homeland with heroic determination. British, French and Anzac troops ashore suffered every kind of privation and danger. Occupying coastal trenches under almost continual bombardment, they were hurled again and again into attacks that gained only a few feet of soil, at hideous cost.

The Anzacs quickly developed a reputation for being the most aggressive fighters on the peninsula. Their trenches were filled with a wild, almost berserk excitement. Anzac soldiers held in reserve could not bear to be left out of the fight. They would offer to pay for a place on the firing line. In one trench, two Australian soldiers actually fought one another with their fists for a vacant position on the parapet. The fighting spirit of the Anzacs inspired all those who witnessed it. To quote Moorehead once again:

No stranger visiting the Anzac bridgehead ever failed to be moved and stimulated by it. It was a thing so wildly out of life, so dangerous, so high-spirited, such a grotesque and theatrical setting and yet reduced to such a calm and almost matter-of-fact routine. The heart missed a beat when one approached the ramshackle jetty on the beach, for the Turkish shells were constantly falling there, and it hardly seemed that anyone could survive. Yet once ashore a curious sense of heightened living supervened. No matter how hideous the noise, the men moved about apparently oblivious of it all, and with a trained and steady air as though they had lived there all their lives; and this in itself was a reassurance to everyone who came ashore.

Even under heavy shelling, the Anzacs would take the piss. One Australian reportedly shouted, “Play you again next Saturday”, whilst shooting at a retreating Turk. When some poor devil had his head blown off on the toilet, the soldiers laughed. They talked about death in a totally irreverent way (e.g., "He copped it in the head"). They treated their superiors with the same irreverence. They often refused to salute British officers, whom they regarded as effete. Their own officers struggled to control them. Nothing their superiors said could stop them from bathing in the Aegean sea under heavy fire.

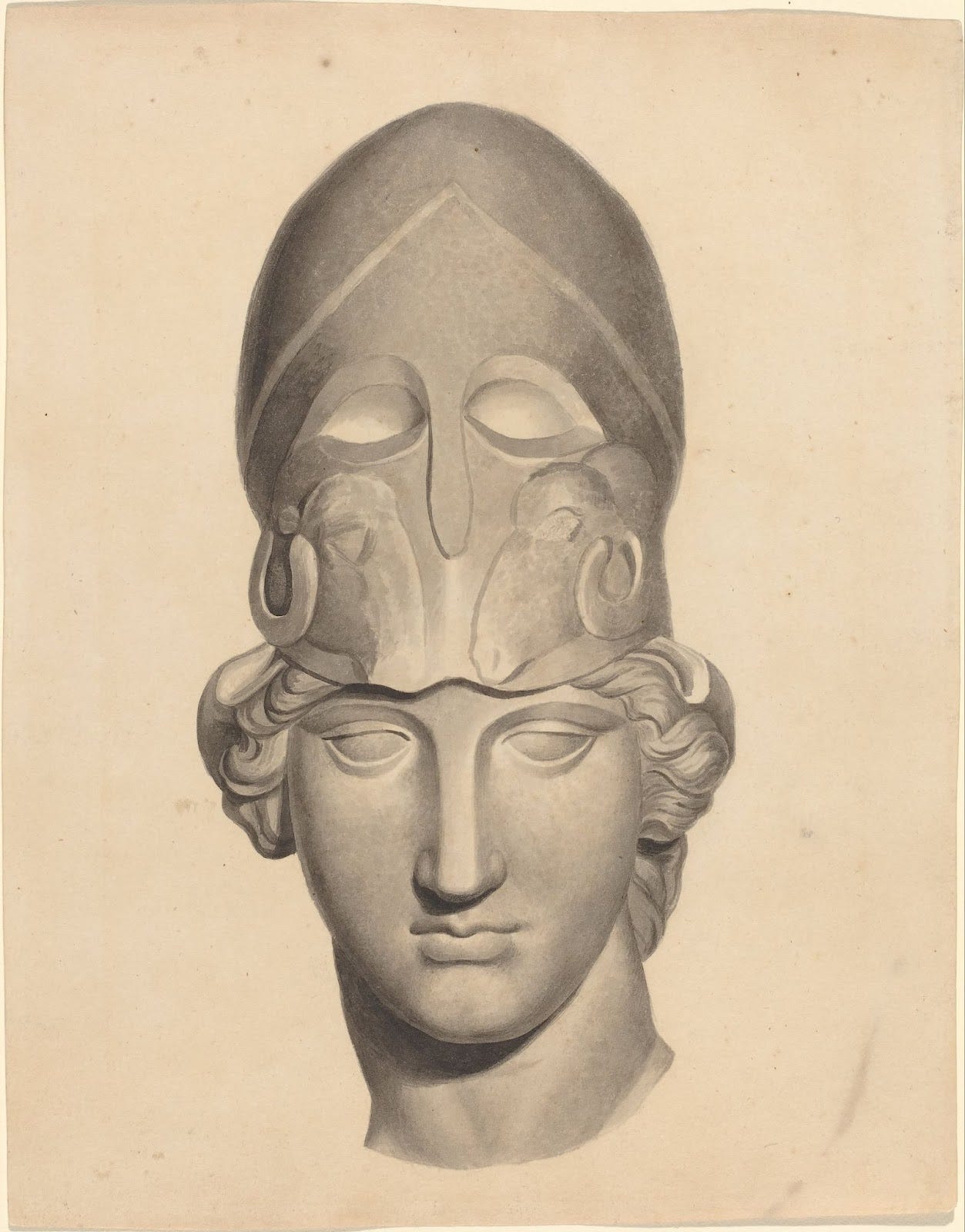

The Anzacs bathed in the same sea that Achilles and Agamemnon had sailed in three millennia earlier. They fought in a land steeped in classical legend. This classical connection was not lost on observers of the time. Upon witnessing the Anzac troops, the Scottish writer Compton Mackenzie said:

As a child, I used to pore for hours over those Flaxman’s illustrations of Homer. There was not one of those glorious young men I saw that day who might not himself have been Ajax or Diomed, Hector or Achilles. Their almost complete nudity, their tallness and majestic simplicity of line, their rose-brown flesh burnt by the sun and purged of all grossness by the ordeal through which they were passing, all these united to create something as near to absolute beauty as I shall hope ever to see in this world.

An Athenian Temple in the Antipodes

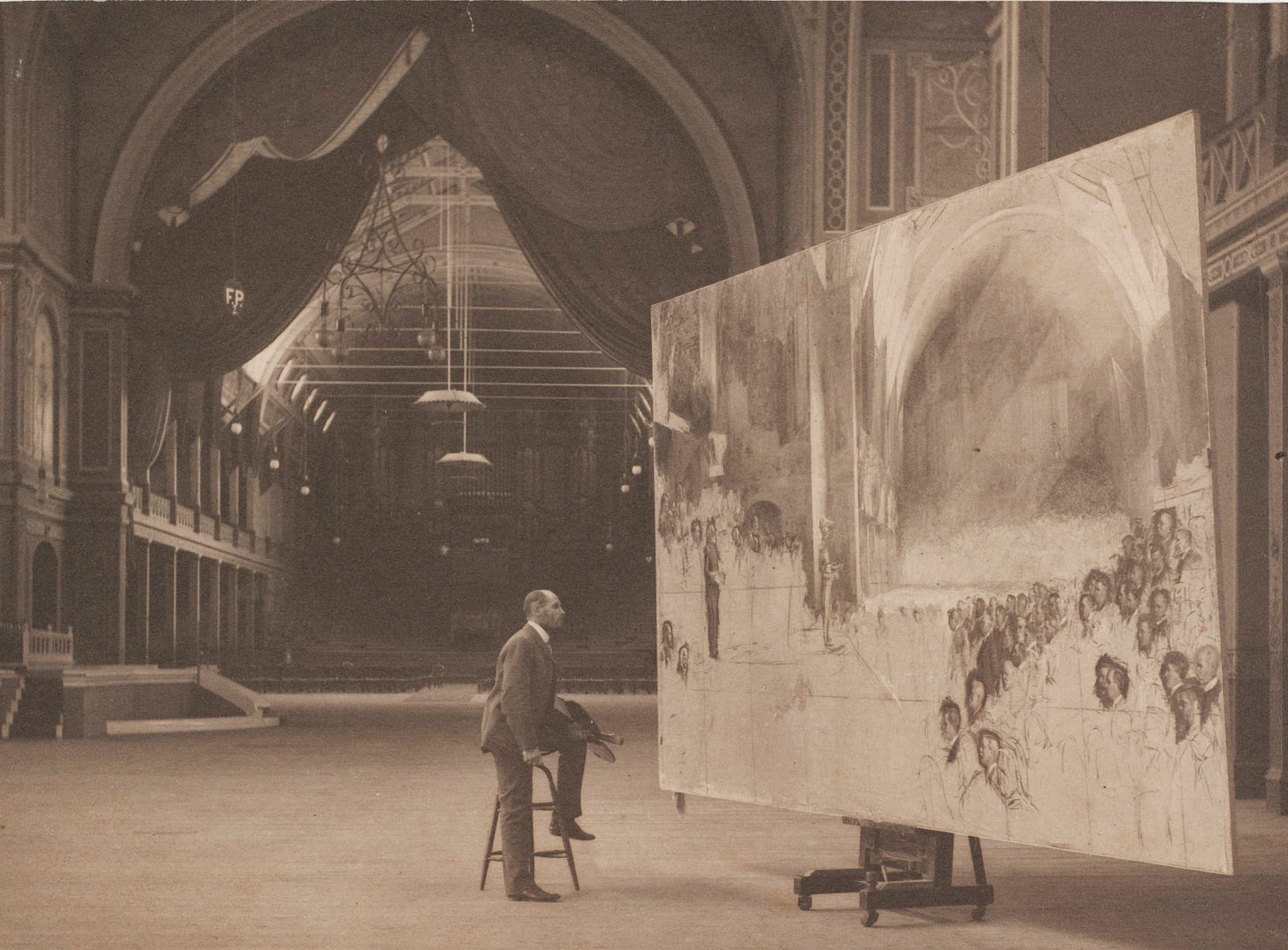

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Anzac memorials sprung up across Australia. These memorials were secular, yet sacred. They had the qualities of what Rousseau called a "civil religion." Civil religion lends the secular an aura of the sacred. It binds nations together through shared places, rituals and ceremonies. In the trenches of Gallipoli, Australia gained martyred heroes to venerate, sacred battles to celebrate, and hallowed ground to commemorate. In other words, it gained what it had previously lacked: the foundations of a civil religion.

Much to the frustration of the clergy, this civil religion seemed to take precedence over the Christian religion. In 1965, Anzac Day fell on a Sunday. The Ceremony was scheduled for 9 a.m., meaning people had to choose between honoring the dead or attending Church. The prominent Methodist Minister, Alan Walker, was outraged that Australians were forced to choose between “Pagan worship of the state and the worship of God.”

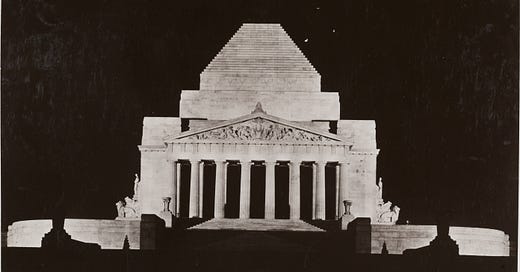

Walker called the Anzac ceremony “Pagan” because it resembled the religion of antiquity, were heroes were deified and ancestors were worshipped. Australians worship and deify the Anzacs in much the same way. This worship is reminiscent of an Ancient Greek hero-cult, and The Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne strongly resembles an Ancient Greek temple.

The Shrine was designed by architects Phillip B. Hudson and James H. Wardrop. They modelled it on the Parthenon, which was built to commemorate Greece’s victory over the Persians. Hudson chose a site in Melbourne that he believed “was similar to the Athenian Acropolis” (though it must be said, Remembrance Hill falls somewhat short of the Acropolis).

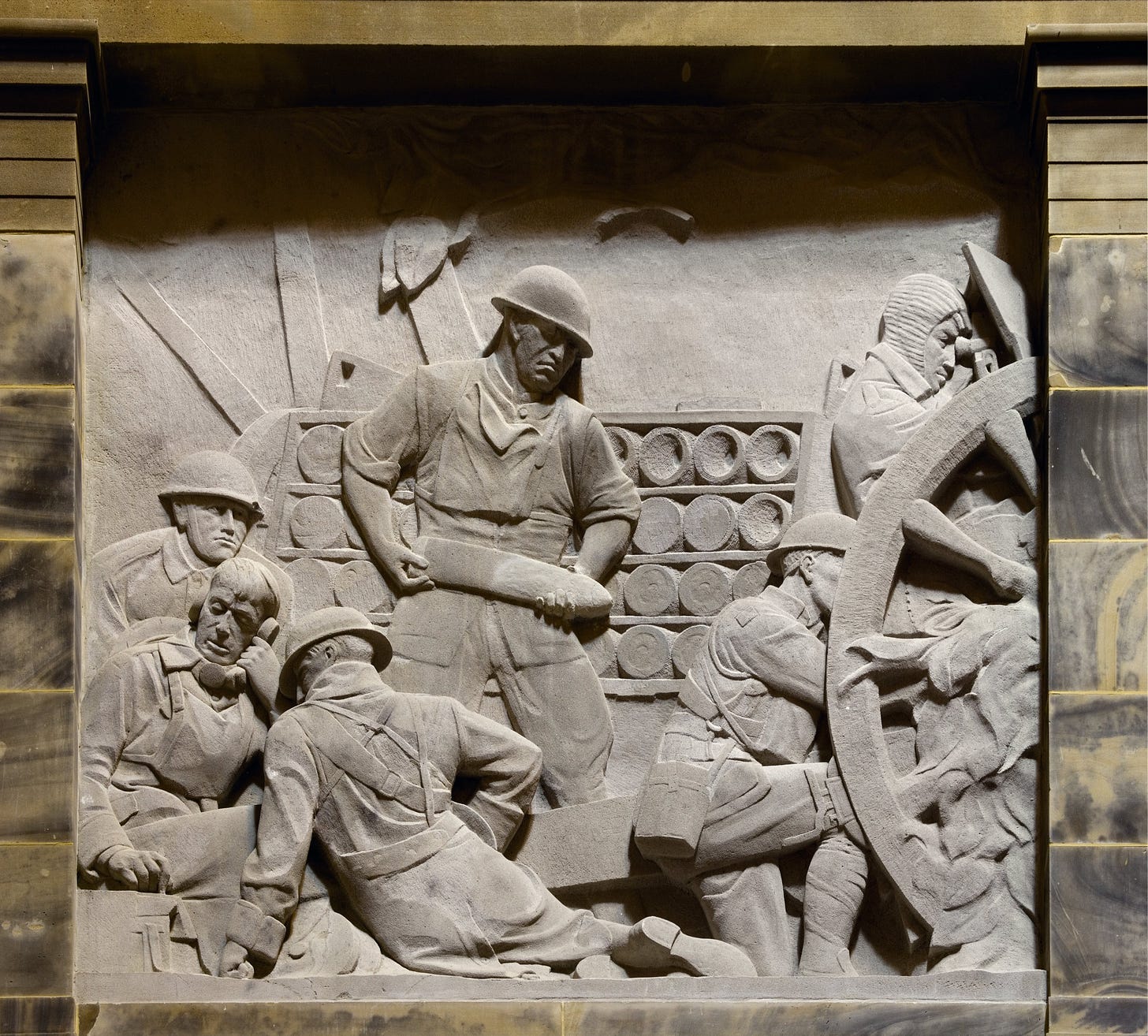

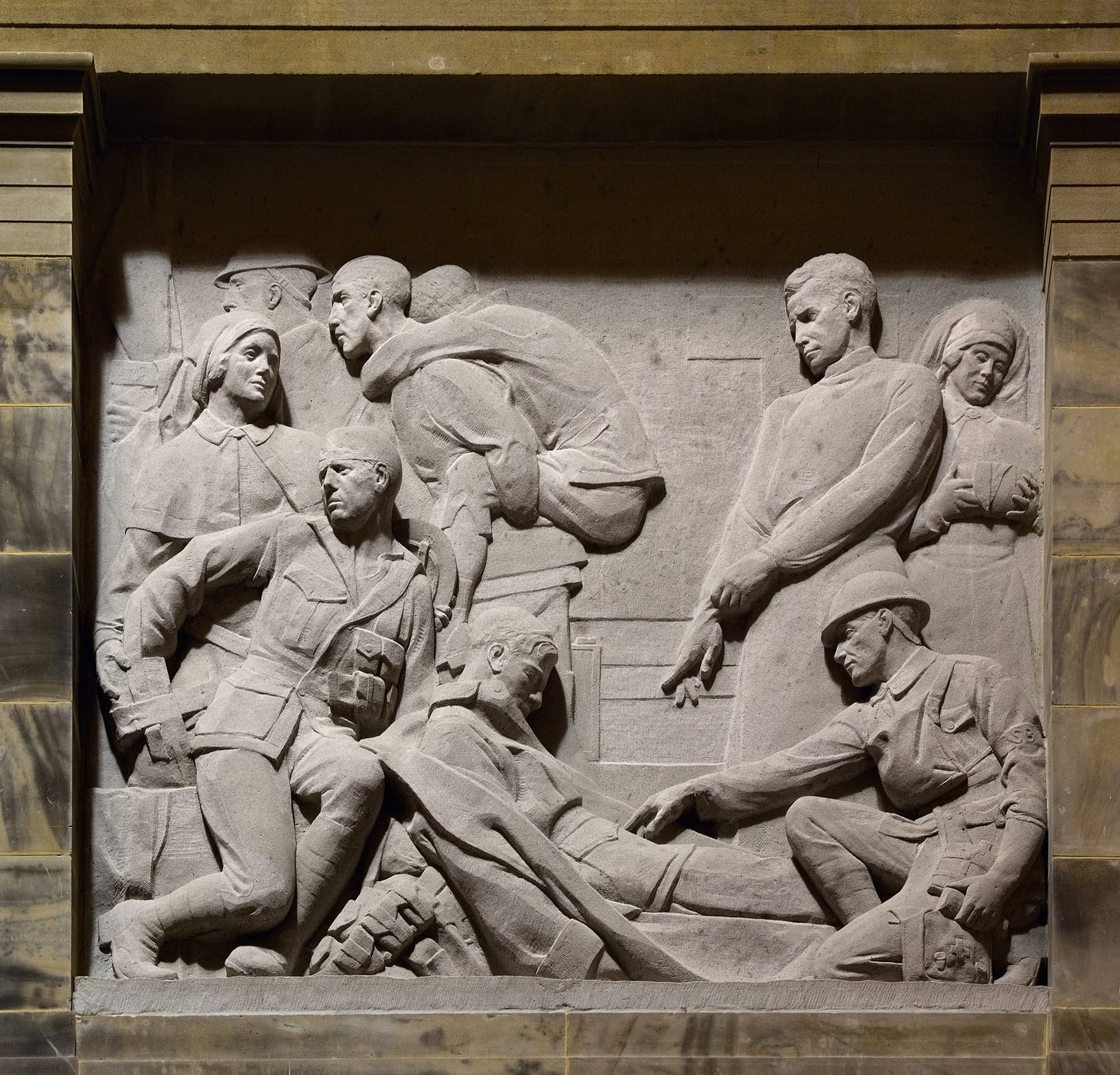

The base of The Shrine is a Doric temple, its roof is a monumental tomb, and the whole structure is topped with an Athenian victory monument.

At the heart of the Shrine is a sanctuary. A stone frieze runs along its upper walls. Like the frieze in the Parthenon, it depicts citizens fulfilling their duty to the state. On the north wall, we see the Australian infantry forces. On the east, we see the Royal Australian Navy and Flying Corps. On the south, we see the Australian Light Horse, and on the west, we see the Medical Corps. Beneath the frieze stand eight Ionic columns, guarding the central Stone of Remembrance, which reads: “Greater love hath no man.”

Upon viewing the recently completed Shrine, a journalist for The Age wrote, “what I have seen has left a strange and reverent feeling – the glory of ancient Greece has been recreated by these artists.” Another writer, Ambrose Pratt, went even further, calling the Shrine “the most majestic and the most perfect example of classical Grecian Architecture the world contains.”

Pratt went on to write a book on The Shrine. In this book, he compares the Anzacs to “the Grecian heroes whom Homer portrays”, and argues that Gallipoli was our Trojan War:

More than eleven centuries before the Christian era the heroes sung by Homer in the Iliad and Odyssey answered the call of their King, and rallying to his aid from all the States and Colonies of Greece, they left their homes and sailed across the sea to contend for many years against Troy. In A.D. 1914 the people of Australia heard a similar call and in like manner they answered – crossing many waters in their ships and scattering their blood and treasure in a protracted and terrible conflict in alien and inhospitable lands.

The Shrine is a Grecian temple dedicated to an Australian hero-cult. This hero-cult is at the heart of our national mythology.

Twilight of the Idols

But Australian nationalism is dead. And we have killed it. How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? Is not the greatness of this deed too great for us? Must we ourselves not become gods simply to appear worthy of it?

No, we don’t need to become gods. We need to become Vietnamese. Australian nationalism is being replaced by left-wing internationalism. For the latter to be successful, it must supplant the former.

Christianity didn’t supplant Paganism in Europe by outright destroying it. Instead, it co-opted and appropriated it. Pope Gregory told missionaries in Anglo-Saxon England to convert pagan temples, rather than destroy them. The Church Fathers redirected the pagan celebration of the sun into the celebration of the Son by converting a solar festival into Christmas. And Pagan reverence for female deities was redirected toward the Virgin Mary. To quote the German historian, Carl Erdmann:

When the church encountered pagan elements that it could not suppress, it tended to give them a Christian dimension, thereby assimilating them.

Leftism operates with similar pragmatism. When it encounters nationalist elements that it cannot suppress, it gives them a leftist dimension, thereby assimilating them.

One nationalist element that the left cannot destroy is Anzac Day; it has proved much more resistant to attack than Australia Day. The left must, therefore, subvert and assimilate it. One of the ways it does this is by inserting a "Welcome to Country" ceremony into Anzac Day proceedings. The message is subtle yet unmistakable: fly your flags, play your bugles and bagpipes, but don’t forget whose land this is.

On the 25th of April, 2025, the attempted assimilation met with unexpected resistance. As the Welcome to Country was read aloud at the Shrine, members of the crowd began to boo. The worshippers of Australia’s old hero-cult rejected the new religion.

Australia’s Prime Minister has said that these hecklers “must face the full force of the law.” Cuckservatives have condemned them for disrupting the “solemnity” of the dawn service. I find all this talk of solemnity tiresome. As

has pointed out, "there's a certain dishonest performativity in the pretense of grief for the deaths of people we never knew, who fought for reasons that we have turned our backs on." The Anzacs didn’t fight for a multi-cult or “Bunurong Country.” They fought for white Australia.People sacrifice for their country because it is their country. Today, white Australians are constantly reminded that this country is not theirs. That's why they increasingly refuse to serve in its armed forces. That’s why the Australian Defense Force has opened its ranks to non-citizens, and started recruiting Papua New Guineans. As much as I like the idea of a Papua New Guinean Cannibal Corps, I don’t think we should be outsourcing our defense to foreigners. I think we should defend our own country. But in order to do that, we need to believe that it is ours.

Great article, although far too complimentary to the English re: Gallipoli, imo. Do you know anything about Australian-Celtic roots?

Incredible post, a tour de force of historical knowledge apparently lost to most Australians, and certainly unknown to the rest of the world.