Chesterton's Microscope

Why Thinking Big Makes Your Life Small

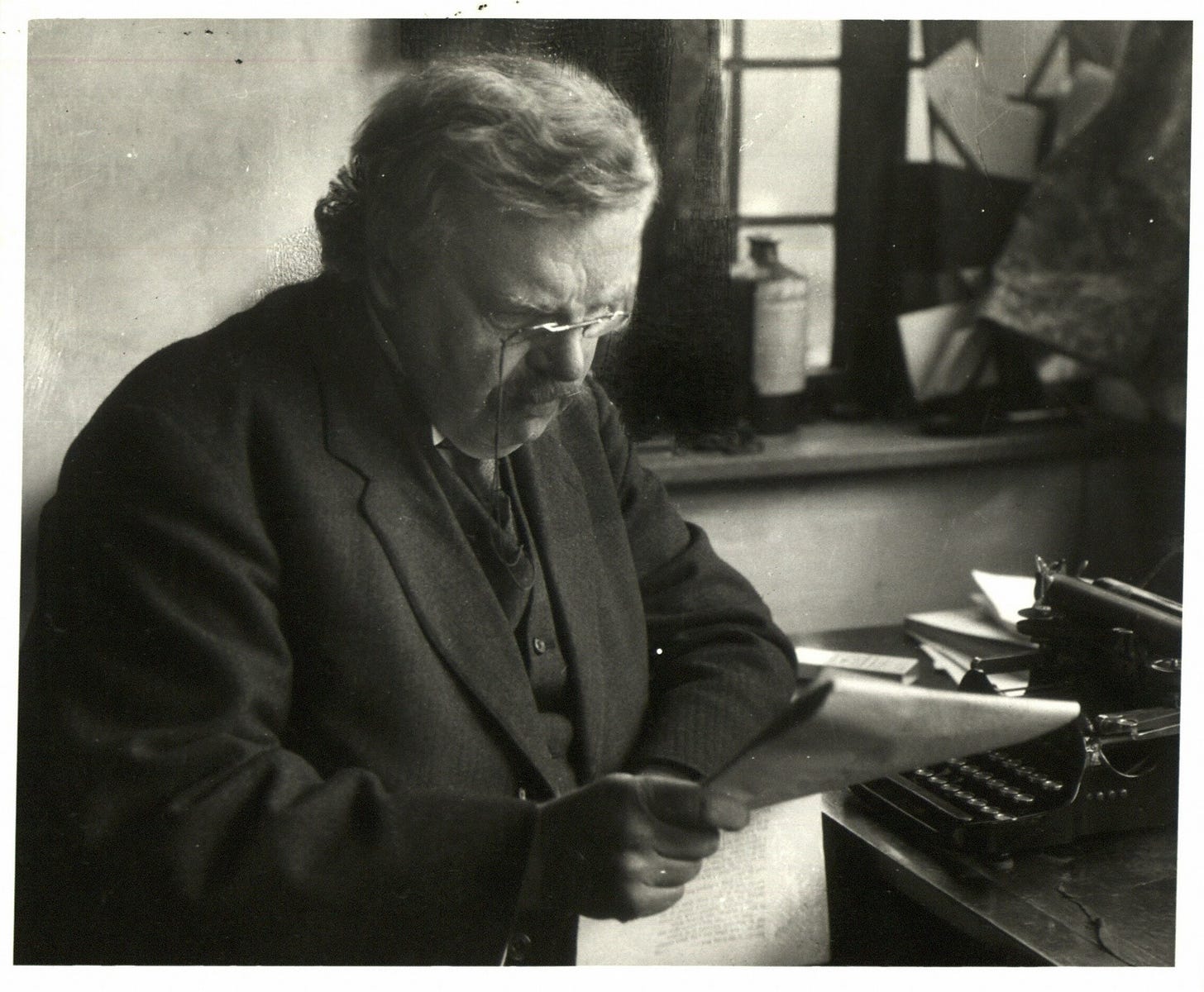

You’ve all heard of Chesterton’s Fence. It’s one of those eponymous principles that people like to invoke, like Occam’s Razor, the Lindy Effect, or Parkinson’s Law. But have you heard of Chesterton’s Microscope?

Probably not, because as far as I can tell, Chesterton’s Microscope doesn’t exist. Or at least, not yet!

People seem to like these eponymous principles, probably because they compress complex ideas into memorable heuristics. I.e., instead of talking about epistemic humility and second-order effects, you can just say ‘Chesterton’s Fence.’ Or instead of explaining the dangers of unnecessary complexity, you can just say ‘Occam’s Razor.’

In this piece, I hope to coin an eponymous principle. Namely, Chesterton’s Microscope. Ideally, it gets its own Wikipedia page (to reach such lofty peaks!). But it will probably join the vast graveyard of failed eponyms. But whether it fails or not doesn’t matter, dear reader, because you will know about Chesterton’s Microscope. And I sincerely believe it’s a heuristic that will improve your life.

So, what is Chesterton’s Microscope?

In his 1905 book, Heretics, G.K Chesterton said: ‘the telescope makes the world smaller; it is only the microscope that makes it larger.’ Too true, Gilbert!

A telescope compresses large things into a narrow field of view. An entire mountain range can fit within its eyepiece, and objects far away suddenly appear nearby. Objects nearby, by contrast, become an indistinct blur.

A microscope does the opposite. It takes something small and makes it vast.

In this life, you can be a telescopist, or you can be a microscopist. Which is to say, you can study large things and live in a small world, or you can study small things and live in a large world.

Chesterton’s Microscope is the principle that by focusing on small, proximate things your world actually expands. This principle has political, cultural, and environmental implications.

But perhaps most importantly, it has personal ones. If you are highly online (you are), and if you spend a lot of time thinking about politics (you do), you are almost certainly a telescopist.

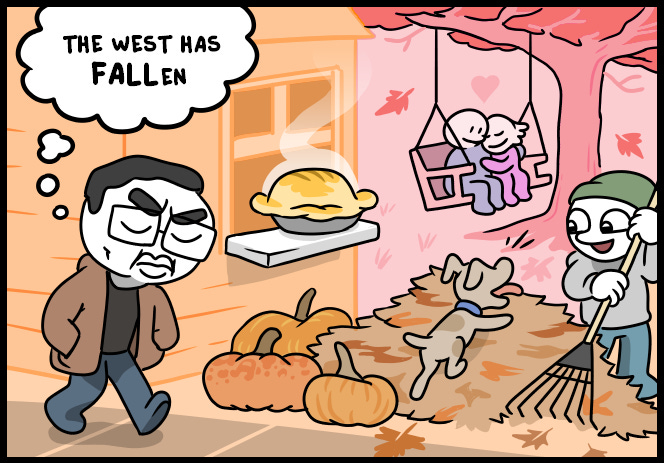

The telescope brings distant crises into sharp focus. You’re monitoring the situation in Venezuela. You’re worried about South Korean birthrates. And you’re concerned about the fate of Western civilization. Meanwhile, your immediate surroundings are an indistinct blur.

Jordan Peterson’s ‘clean your room’ message resonated because it was microscopic, rather than telescopic. Peterson himself went on to become the telescopist par excellence, talking about every culture war issue du jour. But I think Peterson’s ‘clean your room’ message was good. Because let’s be honest, your room does need to be cleaned. And maybe you should, like, work before you try to incite a worker’s revolution.

Now, of course, ‘clean your room’ was never actually about cleaning your room. It was about addressing your small problems before you try to address society’s large ones. Because your small problems aren’t actually small. They impact you a lot more than, say, Greenland’s strategic military importance to America. Because the big things, like Greenland (which certainly is big!), impact you in small ways. But the small things, like your room, impact you in big ways. And yet, you obsessively focus on the former, often at the expense of the latter.

But what would your life look like if you invested your time differently? To paraphrase Max Meursault’s fantastic essay, Politics Is Worse Than Video Games, Drugs and Porn Combined:

What would your children’s lives be like if you took those 10, 20, 40, or 100 hours a week for 52 weeks over 5 decades, somewhere between 26,000 and 260,000 hours of time, and spent them on pretty much anything else besides politics? What would it look like if you dedicated a hundred hours to reading a dozen books on parenting or finance or business or any number of other actually useful skills?

In other words, what would your life look like if you were a microscopist, rather than a telescopist? Almost certainly better. Not least of all, because you wouldn’t be depressed.

Telescopes and Learned Helplessness

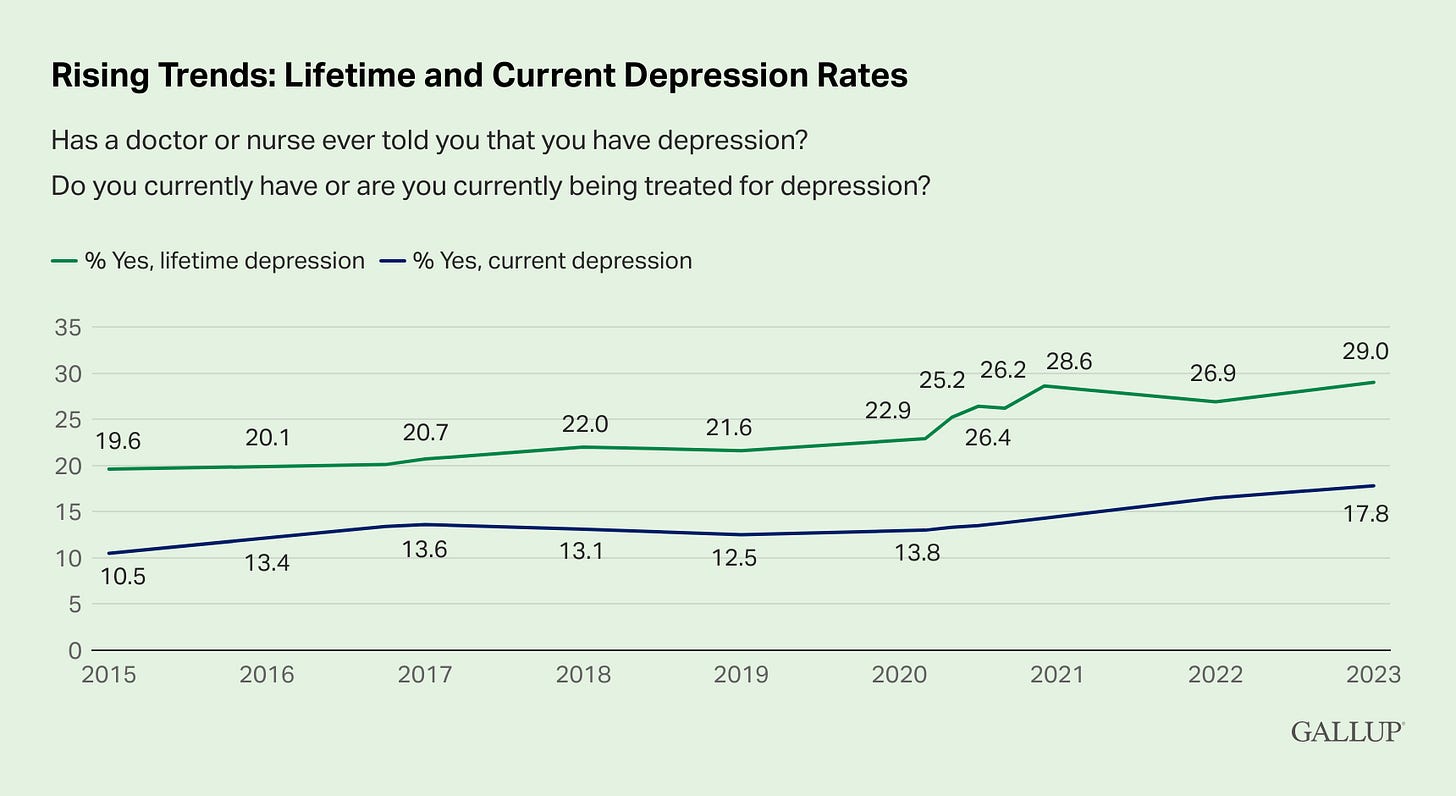

According to a 2023 Gallup study, 29% of U.S. adults have been diagnosed with depression at some point in their lives. This number has increased by 10 percentage points since 2015.

Some attribute this rise to improved awareness and better diagnosis, while others blame secularism, social alienation, and the prevalence of digital technology. Both these explanations are probably true, but there’s a third that I want to explore.

I think the upsurge of depression can be attributed to an epidemic of learned helplessness.

A situation is helpless when there is nothing you can do to change it. Learned helplessness is the belief that there is nothing you can do, in any situation, to change anything.

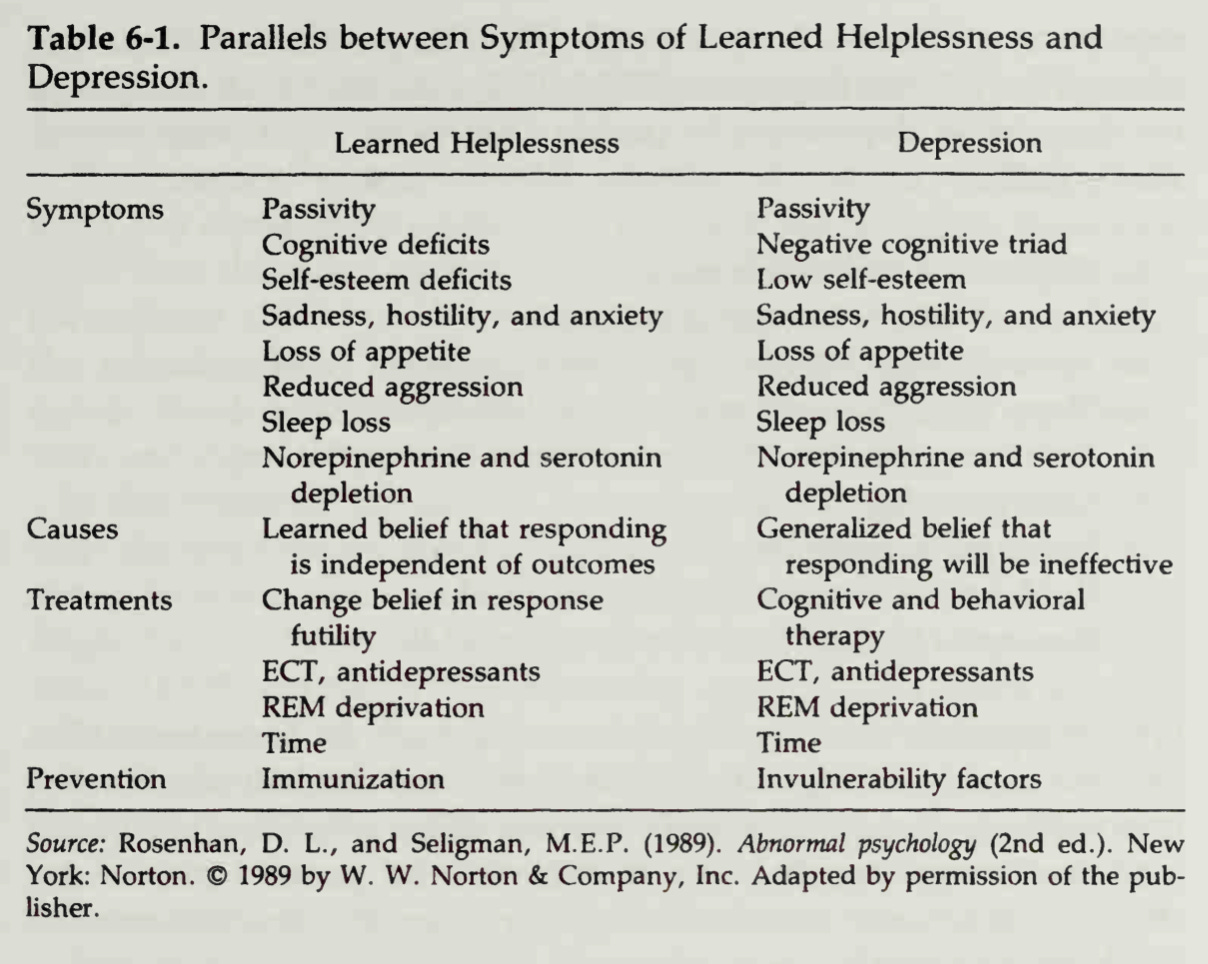

The psychologist, Martin Seligman, noticed striking similarities between the symptoms of depression and learned helplessness. So much so, that he concluded that learned helplessness is depression.

I think the depression rate is increasing because people increasingly feel helpless. But this answer only raises another question: why do people feel helpless?

Now, instead of saying the usual cliché—‘it’s the phones!’—I could say, ‘it’s the telescopes!’ But really, it’s the phones.

Your phone is a telescope. It exposes you to everything, everywhere.

Thirst trap. Baby crying in rubble. Thirst trap. Drone strike. Gym motivation. Mass shooting. Morning routine. Subway stabbing.

Suffice to say, this is not normal. Your limbic system was not designed to process mass shootings between thirst traps. And you’re not supposed to know about all the world’s problems. Particularly because there is pretty much nothing you can do about them.

To illustrate this point, imagine looking through a telescope. You see Will Martin brutally murdering Richard Hanania. You’re horrified. The tragic loss of elite human capital!

Somebody should do something. Somebody should stop it. Perhaps you should stop it! But how? The murder is happening ten kilometers away. You’re standing on a hill with a telescope. In other words, you can see everything, but do nothing. You are helpless.

You experience an analogous dynamic daily.

You monitor the situation in Gaza. You follow the independence movement in West Papua. You have strong opinions about the disputed territory in Nagorno-Karabakh.

But what does all this monitoring and opining accomplish? Precisely nothing, because these situations exist entirely outside of your locus of control.

Frequent exposure to bad situations outside of your locus of control creates learned helplessness. In other words, you don’t just feel powerless about West Papua, or global warming, or whatever. You feel powerless in your own life.

At the risk of belaboring the metaphor, let’s return to our telescopist on the hill. He watches Will Martin kill not only Richard Hanania, but a veritable who’s who of elite human capital (Nathan Cofnas, Razib Khan, etc).

Eventually, our telescopist puts down his telescope, only to find Will Martin right in front of him. He could run. But he doesn’t. After watching dozens of murders he couldn’t prevent, he has learned that murders can’t be prevented. In other words, he has learned helplessness.

Something similar happens to extremely online extremists. Like the telescopist watching distant murders, they are frequently exposed to problems beyond their reach. Constant exposure to these problems produces learned helplessness. They become black pilled. They begin to believe that it’s over. And not just for the climate, or the white race, or whatever their particular political obsession is—but for everything, including the tractable problems in their own lives.

Conclusion

But all of this is decidedly telescopic. Let’s stop talking about Gaza, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Richard Hanania. Let’s start talking about you.

How can you apply Chesterton’s microscope to your life?

Broad recommendations are, of course, telescopic. Nonetheless, here are some small things that almost everyone can do to become more of a microscopist:

Media fast.

Learn about your family history.

Learn about local history.

Learn about local fauna and flora.

Meditation.

Get involved in local politics.

Become a regular at a local cafe/restaurant/bar.

Now, of course, the microscope is not without its flaws. You can become so absorbed in the small things that you become blind to the big things. But the big things aren’t going to become blind to you. You may not be interested in war, Leon Trotsky once said, but war is interested in you. And so too are politics, economics, and the environment.

So yes, the telescope has its place. But if you’re reading this, you almost certainly spend too much time looking through it.

So put down the telescope, and pick up Chesterton’s Microscope™.

P.S. if you’d like to read more about learned helplessness, click here.

Great advice, well written.

How do begin microscoping? Take a pen and paper. Draw a small circle. Inside that, list everything you can personally influence.

That’s all you should focus on. Everything outside your circle of influence will likely drive you crazy.

You know it’s over when the Hitlerians (correct me if I am wrong) say “just go outside bro” 💔