Life is a game. The way you dress, speak, and carry yourself reveals your position on the scoreboard.

Like all games, there are rules. They’re not written down, but they constrain your thoughts, actions, and behavior.

This game compels you to scheme and to innovate; to push yourself to new limits in order to win. It shapes your opinions, career choices, and spending habits. It influences where you live, what you study, and what you pretend to enjoy (but I’m sure you actually do enjoy David Foster Wallace, dear reader).

I am talking, of course, about the status game.

This game is inside us. We can’t help but play it. For millions of years, high status meant better mates, more food, greater security. Low status meant genetic extinction, inceldom, zero hoes.

Status-seeking is hardwired into our brains. It is universal, but its expression is context-dependent. What codes as high status varies by ecological niche. In the Stone Age, Cro-Magnon man would stomp, yell, and flex in front of women. This was scarcely more sophisticated than a silverback gorilla thumping his chest. Me strong. Me loud. Me get woman.

Suffice to say, this ooga booga behavior wouldn’t be appreciated by members of the Royal Sydney Yacht Club. In rarefied environments, displays of raw strength are vulgar. They signal an unfortunate proximity to the brutish classes. But in other ecological niches, chest-thumping codes as ‘alpha’ rather than apish. El monstruo Texano drives around in a RAM and injects steroids. Like his paleolithic ancestors, he signals status through physical dominance. In the American south, this is an adaptive strategy. In America’s coastal regions, it is uncouth, proleish, and irredeemably low status.

In short, status is contextual. What’s considered high-status in one environment can be irredeemably low-status in another. There isn’t a singular way to be high status. To quote W. David Marx, ‘There is a Hollywood entertainment mogul way of being high status that is distinct from that of Texan oil magnates.’

To make matters even more confusing, the same behavior in the same environment can take on radically different meanings across time.

Elites adopt trends early to distinguish themselves from the masses. This imbues the trend with prestige, which soon attracts imitation from below. Elites cannot associate with lowbies, and so they abandon the trend. No matter how much they once cherished a piece of fashion or furniture, they will discard it the moment it fails to demarcate them from the vile hordes.

The internet now enables elite conventions to diffuse rapidly through every layer of society. It doesn’t take long for the proles, and even the lumpen-proles, to copy and counterfeit elite trends. This creates a frantic chase and flight dynamic: low-status individuals chase high-status individuals by imitating their conventions, which forces high-status individuals to take flight.

This chase and flight dynamic creates serious problems for clothing brands. In the 1980s, Ralph Lauren appealed to the WASP elite by drawing on English aristocratic aesthetics. For a time, Ralph Lauren signaled upper-class status.

But in Australia, eshays began wearing Ralph Lauren Polos. The word eshay derives from the Pig Latin word for ‘sesh’, meaning marijuana smoking session. It describes a subculture that originated in Western Sydney, but soon spread throughout Australia. Eshays enjoy smoking weed, graffiti, shoplifting, grievous bodily harm, and—most importantly for our purposes—Ralph Lauren. As a consequence, the brand is now lumpen-prole coded.

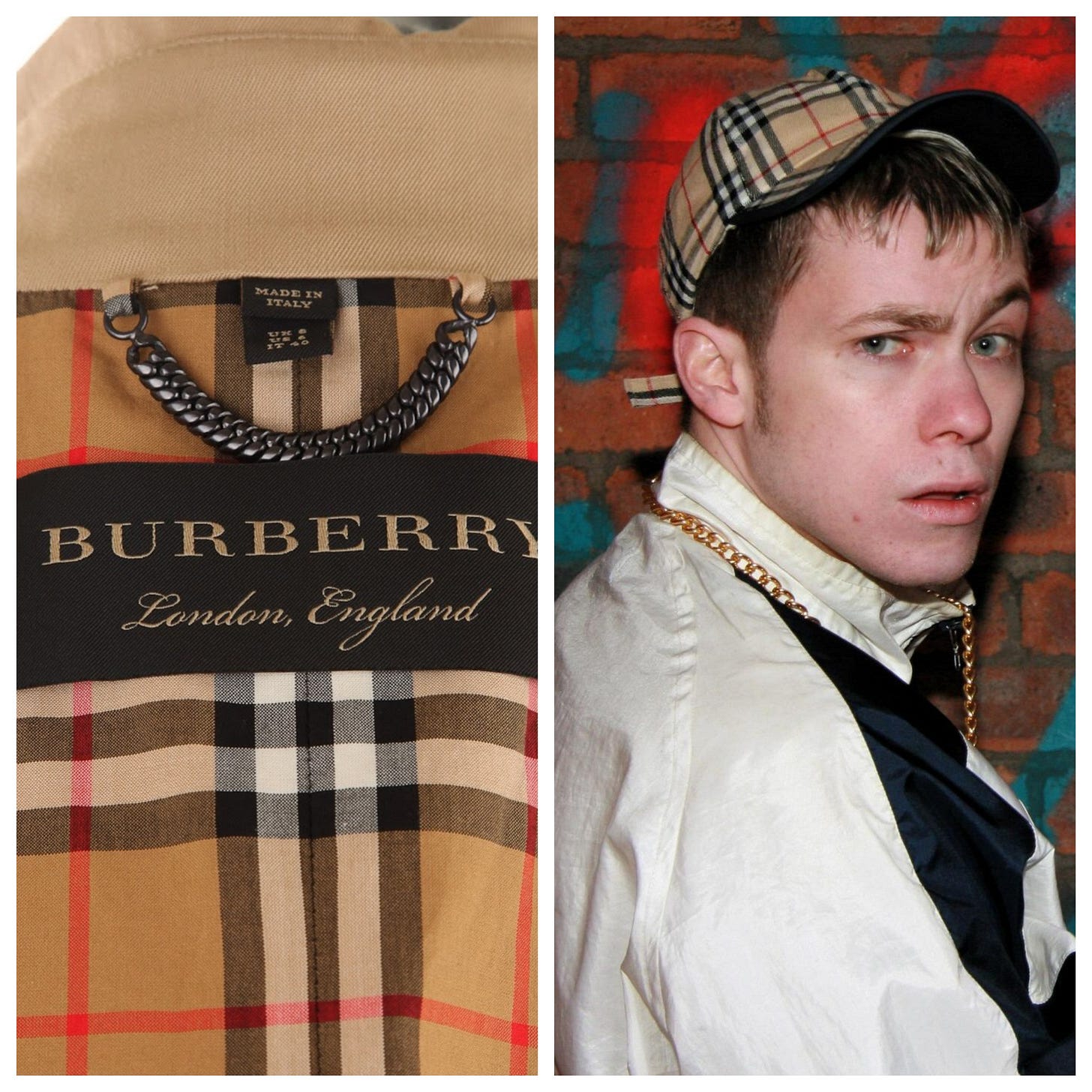

Something very similar happened to Burberry in the United Kingdom. Their classic tartan print went from chic to Chav when football hooligans began sporting counterfeit versions. Justine Picardie, then editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar UK, noted:

Burberry had become so associated with a downmarket image . . . its incredible legacy has become associated with the cheapest form of disposable rip-off fashion.

There is, in other words, an inexorable tendency for everything to become proletarianised in advanced industrial society. This tendency can be called ‘Prole Drift’. Just as entropy condemns all ordered systems to disorder, Prole Drift condemns all status symbols to proletarianisation.

Now, you’re probably thinking: This status stuff is so complicated. How do I demarcate myself from the vile hordes without having to constantly adopt new trends? How do I make sure I’m not doing anything proleish, vulgar, déclassé, or tragically middle-brow?

Fear not, dear reader. This gentle introduction to status will answer all of your questions. It will explore the full range of the status spectrum, from prole to patrician, and show you how to act, eat, and dress like the latter.

Explicit vs. Implicit Status

But first, what is status? It derives from the Latin word statum, meaning ‘the way something stands.’ In English, we use it to describe an individual’s standing in the social hierarchy.

In Medieval England, this hierarchy was explicit. The King and Queen were at the apex of the hierarchy. Below them sat dukes, earls, and barons, followed by knights, merchants, artisans, and finally peasants.

This rigid hierarchy was legally codified and ruthlessly enforced. Sumptuary laws dictated what each class could wear, eat, and own. These laws forbade the ‘outrageous consumption of meats and fine dishes’ among the lower-classes, and stipulated that ‘no knight under the estate of a lord, esquire or gentleman, nor any other person, shall wear any shoes or boots having spikes or points which exceed the length of two inches.’

These laws were not unique to Europe, but existed in most societies. To quote W. David Marx, ‘Aztec warriors marked their status through embroidered cotton cloaks, lip plugs, turquoise and gold earrings, and bright feathers—all of which were forbidden to commoners.’

Sumptuary laws were essentially designed to prevent Prole Drift. By legally prohibiting lower-class people from adopting upper-class fashions, elites could gatekeep their status symbols. In Medieval England, the equestrian knight on Burberry’s logo could have charged down Chavs who dared wear counterfeit tartan.

In addition to adhering to sumptuary laws, plebs were also expected to show ritualized deference to their superiors. In England, this was done by capping, kneeling, bowing, and curtseying, among other things. But not everyone did this. The Quakers, for example, steadfastly refused to give ritualized deference to their social superiors. This enraged the upper classes. One story from David Hackett Fischer’s book, Albion’s Seed, captures this rage perfectly:

While out riding one day, Sheriff Parker met a Quaker tenant named James Smithson who refused to remove his hat. ‘Knowest then me not?’ the sheriff demanded. ‘I know thee,’ the Quaker replied. ‘Who am I?’ ‘Thou art my Landlord.’ ‘Am I so!’ the sheriff said. ‘But I will teach thee.’ The Sheriff swung his heavy rod and struck James Smithson full in the head. Then he pulled off the Quaker’s hat, and ‘did continue striking him on the head till his rod broke off so short that he cast away what was left of it and stroke him with his hands while he pleased.’ A little later Smithson met the sheriff again, and once more refused to give hat honor. ‘Is there no honor belongs to a landlord?’ the sheriff asked plaintively. ‘I honor thee with my rent,’ Smithson replied, ‘other honor I have not for thee.’ Once again the sheriff ‘struck him in the head with a rod, and pushed off his hat and did strike him in the head and face til the blood came.’

The Quakers weren’t the only people who resented this rigid social order. The rising merchant class—the grande bourgeoisie—had their own frustrations.

During the early modern period, the merchant class began to rise. International trade, colonial ventures, and early industrialization enabled them to accrue fortunes that often dwarfed those of hereditary nobles. And yet, the nobles continued to treat them like Vietnamese fishmongers. They had no respect for commerce, which they saw as dirty and degrading. To quote William Doyle’s book, Aristocracy and its Enemies:

It was not only inappropriate, but positively illegal for nobles to engage in retail trade, embrace base professions, farm for rent, or generally work with their hands. The penalty for such demeaning activities was dérogeance, derogation or loss of nobility… The principle of dérogeance was underpinned by deep and persistent anti-commercial prejudices.

Anti-commercial prejudices manifested in a variety of ways. Merchants were excluded from court, barred from elite social clubs, and frequently spoken down to by impoverished nobles. Suffice to say, this bred intense resentment among the grande bourgeois. I think this resentment was what really fuelled the revolutions of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. The revolutionaries abolished the nobility, along with their titles and privileges. This was done in the name of liberté, égalité, and fraternité.

But nobody actually believes in égalité, least of all the egalitarians. Indeed, egalitarianism has become a class marker. To be inegalitarian (racist, sexist, homophobic, etc) is prole-coded. It signals that you’re from flyover country, that you shop at Walmart, that you need to educate yourself.

No, we didn’t get equality. A new status hierarchy simply replaced the old one. This new hierarchy is implicit, rather than explicit. Instead of titles and sumptuary laws, we have unwritten rules of taste and behavior that police social boundaries. These rules are often difficult to decipher, not least of all because we have to pretend they don’t exist. Social hierarchy is passé. We’re all equal now. But some people are more equal than others. Unlike the Medieval peasant, we often struggle to identify who is the most equal of all. To quote Paul Fussell:

We lack a convenient system of inherited titles, ranks, and honors, and each generation has to define the hierarchies all over again. The society changes faster than any other on earth, and the American, almost uniquely, can be puzzled about where, in the society, he stands… Belonging to a rapidly changing rather than a traditional society, Americans find knowing where they stand harder than do most.

This gentle introduction to status is designed to help you answer the question: where do I stand? I contend that there are six ranks, or classes, in modern society:

Upper-Upper

Upper

Upper-Mid (UMC)

Mid

Proles

Lumpen-Proles

Like distinct tribes, each of these classes possesses its own customs, rituals, and behavioral codes. By studying someone’s clothing, diet, speech, and leisure activities, you can determine which class they belong to. In this essay, I will outline the distinguishing characteristics of each class, so that you can identify where you sit in the social hierarchy.

Upper-Upper & Upper

It should go without saying that the upper-upper class is staggeringly wealthy. But wealth alone is not sufficient to secure entry into this exclusive stratum. The wealth must be inherited. This inherited wealth ideally stretches back three or four generations. In other words, the upper-upper is old money.

Even in our meritocratic society, old money garners more esteem than new money. Families like the Rockefellers—whose oil empire traces back to the early 1900s—have an aristocratic aura that is totally foreign to the technology brother.

Old money has invented numerous terms to distinguish itself from new money: nouveau riche, parvenu, arriviste, etc. Perhaps my favourite is ‘cashed up bogan’, which Australians use to describe proles who have amassed fortunes. The Australian billionaire, Lindsay Fox, is the archetypal cashed up bogan. He dropped out of school at 16 to become a truckie, perhaps the most prole profession. From there, he managed to build a logistics and transport empire. He is now a multi-billionaire, and one of Australia’s richest men. And yet, he would feel totally out of place among the upper-uppers. In fact, he’d probably feel more comfortable around truck drivers. This is because he lacks the cultural, educational, and social capital that is characteristic of the upper-upper class.

Cultural capital means an appreciation for high culture, such as art, opera, literature and classical music. Educational capital means attending the right schools and universities, such as Eton, Oxbridge, Harvard, Yale, and Princeton. Social capital means connections to elite networks, such as country clubs, alumni associations, and prestigious charitable committees. Fox lacks these forms of capital and is therefore consigned to the upper, rather than the upper-upper, class. No amount of wealth can make up for his proleish physiognomy and unmistakably ocker Australian accent.

Another term for the nouveau riche is ‘young rich nigga’ (Migos, 2013). The young rich nigga—hereafter referred to as the YRN—comes from a lumpen-prole background. They often grew up in housing commissions or ‘the projects’. But through music, crime, or sports, they ‘make it out the hood’.

The YRN signals status through conspicuous consumption. Conspicuous consumption is the practice of buying expensive goods, not for their utility, but to display abundance. The term was coined by the economist Thorstein Veblen, who argued that conspicuous consumption ‘must be wasteful. No merit would accrue from the consumption of the bare necessaries of life’.

When we see Gucci Mane wearing a $250,000 Bart Simpson chain, our instinctive reaction is: that’s retarded. But that is precisely the point. He can afford to waste money on retarded things. Like a Kwakiutl chieftain torching his prized possessions in a potlatch, Gucci Mane can afford to torch money on the most spectacularly stupid things.

In addition to chains, the YRN spend money on Maybachs, Moncler and mansions. These status symbols have low symbolic complexity; which is to say, they can be read and understood by everyone. Even the lumpen-proles know exactly what they mean. Namely, I get money, I get bitches, I’m rich, etc.

By contrast, Old Money favors signals with high symbolic complexity. These are possessions, tastes, and behaviors that only those with high cultural capital can decode. This ensures that their status is legible to insiders, while remaining invisible, or even meaningless, to outsiders.

The most vulgar form of conspicuous consumption comes from the YRN, but conspicuous consumption is a characteristic feature of the nouveau riche in general. Lacking cultural, social and educational capital, they default to the most legible form of status signaling. Old money finds this sort of status signalling distasteful, even desperate.

A core tenet of Old Money’s signaling strategy is subtlety, meaning their status claims should never appear to be status claims. Instead of buying the largest and latest luxury items, they favor understated, antiquated, and patinated possessions. To quote W. David Marx once again:

Old Money taste focuses on “patina,” visual proof of age in possessions. A dulled silver plate, for example, implies that the object has been owned for generations… Crumbling old country estates and castles, collections of old painting masters, cellars of vintage wine, and slightly dented furniture from famed craftsmen all suggest a family that has amassed a formidable set of possessions through the centuries.

This veneration for the archaic even applies to automobiles. To quote Paul Fussell:

The upper class regard the automobile as very nouveau and underplay them consistently. If you buy any kind of car, you provide yourself with the meanest and most common to indicate that you’re not taking seriously so easily purchasable and thus vulgar a class totem.

Such restraint baffles the lower classes, who consider sports cars the ultimate status symbol. To them, Andrew Tate’s Bugatti is the ultimate flex. But to the upper-upper, a Bugatti betrays the fact that he’s from a council estate in Luton. Someone raised in the Cotswolds or Martha’s Vineyard has no need for such overt status signaling, because they can signal status through their etiquette, deportment, gesture, intonation, dialect, vocabulary, and even small bodily movements. Like Odysseus, whose nobility was evident even when shipwrecked and naked, true elites embody their status rather than display it.

In short, the upper-upper favour inconspicuous rather than conspicuous consumption. They practice deliberate restraint, choosing items that whisper rather than shout wealth. Their houses are hidden behind large hedges, and their clothing bears no visible logos or branding. This ‘quiet luxury’ countersignals the nouveau riche, who engage in money-drenched boasting.

But of course, none of this matters, because you are almost certainly neither upper-upper nor upper class.

Upper-Mid

Below the upper classes sits the upper-middle class, or UMC.

Members of the UMC earn more than their middle class counterparts. The mids earn between 75% and 200% of the median income. In Australia, the median income sits at around $65,000. If you earn over $130,000—which is to say, more than 200% of the median income—you qualify as UMC (at least in Australia).

But as we have already established, riches alone do not define class. There are plenty of cashed up bogans earning $200,000 a year digging rocks out of the ground in the Pilbara. Technically, they are upper middle class, but nobody would describe them as ‘classy’.

The FIFO miner with a UMC salary drives a Ford F-150 Raptor instead of a beat-up Commodore ute. He takes holidays in Bali instead of Surfers Paradise. He lives in a McMansion instead of a fibro house. Which is to say, he is rich, but his tastes remain fundamentally proleish. To quote

New Money has the income to signal to their old class cohort that they ‘have it all,’ but their definition of what ‘having it all’ looks like remains firmly rooted in their lower-class mindset.

So this technical definition of UMC–earning over 200% of the median income–doesn’t quite capture what it means to be UMC. What, then, truly distinguishes the upper-middle class?

First and foremost, education. The UMC are not FIFO miners or oil rig workers. They are lawyers, doctors, consultants, and investment bankers. They live in major cities, like New York, London, San Francisco, Sydney, or Toronto.

Which brings us to the second defining feature: location. You might think that location is irrelevant to class. God bless, you may even think that someone can be UMC in Cairns or Mildura. Nothing could be further from the truth.

A doctor working in Mildura, Bakersfield, or Luton has a UMC salary, but they don’t have a UMC lifestyle. When the Sydney surgeon meets their regional colleague at a medical conference, they’ll say something patronizing like, ‘Mildura, how lovely! It must be nice being away from all the hustle and bustle.’ But both of them know it’d be much nicer to be in Sydney’s Double Bay.

Where, then, is one to live? Paul Fussell offers a useful heuristic for American readers, ‘The best places socially would probably be found to be those longest under occupation by financially prudent Anglo-Saxons, like Newport, Rhode Island; Haddam, Connecticut; and Bar Harbor, Maine.’

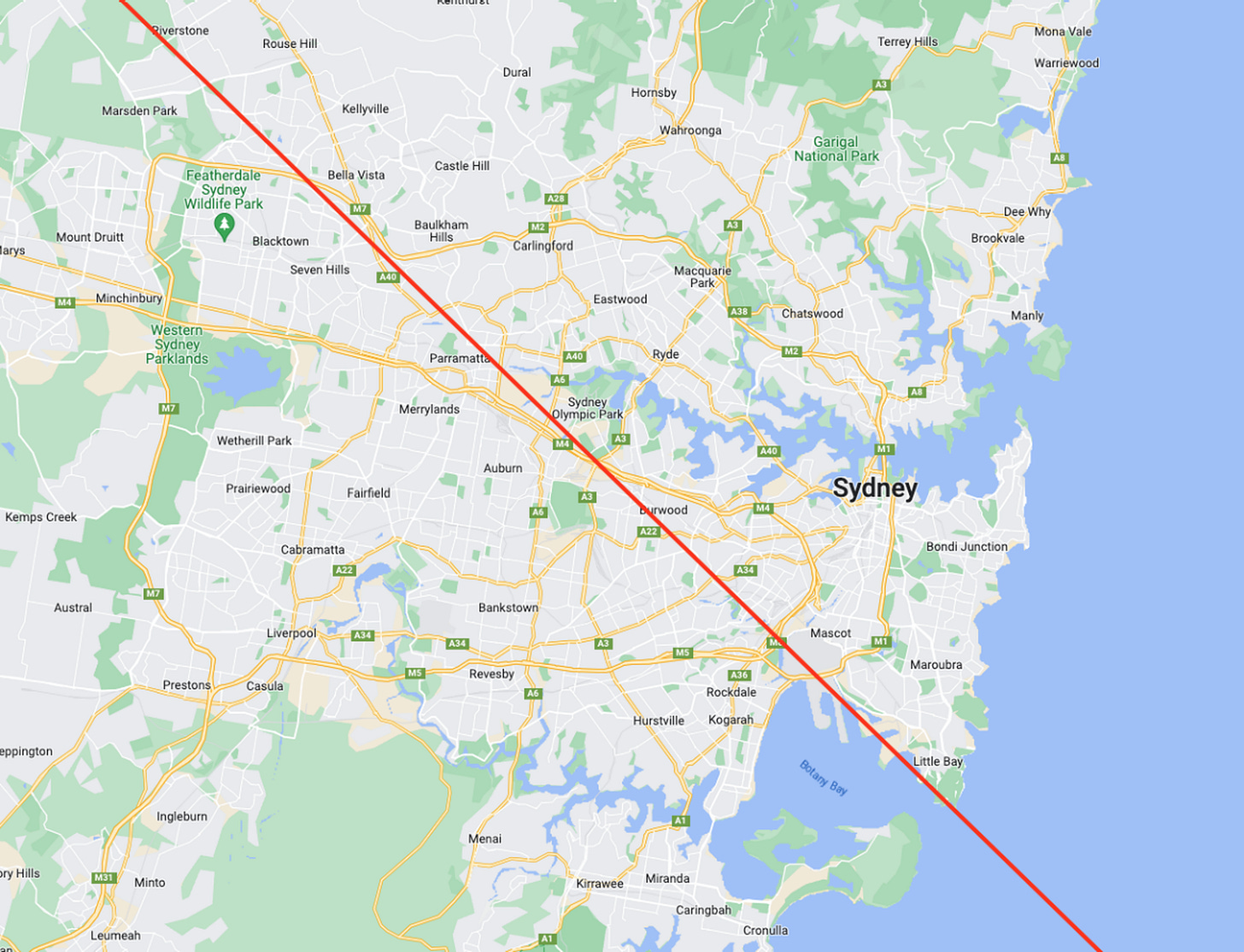

The same principle applies to Australia. Sydney, being the longest-settled location, is also the highest-status. But one cannot live anywhere in Sydney. A member of the UMC has no business visiting, let alone living in Mount Druitt. They must reside within the Harris Farm Ring (also known as the Harris Farm Halo).

Harris Farm Markets is a high-end Australian grocer specializing in organic food. Organic food is UMC coded, not only because it’s expensive, but because it provides an alibi for conspicuous consumption. A UMC shopper can justify spending $52 on a jar of biodynamic kumquat jam by citing ‘reduced pesticide residue’. This alibi allows the UMC to engage in plausibly deniable conspicuous consumption.

Suffice to say, no prole would be stupid enough to spend $52 on jam. And that is why Harris Farm Markets are in Bondi, Double Bay, Paddington, Mosman, and Manly. The median house price within the Harris Farm Halo is around five million dollars.

The third characteristic of the UMC worth examining is their luxury beliefs.

defines luxury beliefs as ‘ideas held by privileged people that make them look good but actually harm the marginalized.’Luxury beliefs, like luxury goods, are expensive. A consultant in the Harris Farm Halo can afford a 2-year lockdown; a small-business owner cannot. A lawyer living in Berkeley Hills can afford to defund the police; someone living in South Chicago cannot. An ‘artist’ (i.e., the son of rich parents) in Fitzroy can afford to reject monogamy; a stay-at-home Mum with three kids cannot.

In short, luxury beliefs signal both cultural capital (familiarity with trendy academic ideas) and economic capital (insulation from their consequences).

Mid

The middle-class are better defined by the work that they do than by their middle income. Mids do headwork (teaching, accounting, engineering) rather than handwork. Typically, this sort of work requires a university degree.

Boomer mids were able to afford homes above Sydney’s Latte Line (also known as the Quinoa Curtain). This line begins around Sydney Airport, and extends North-West past Parramatta.

Above the line, you’ll find cafes serving flat whites, yoga studios, and Montessori preschools. Below the line, you’ll find pokies, public housing and Red Rooster.

Due to soaring property prices, stagnant wage growth, and credential inflation, millennial mids are being pushed below the Latte Line. Either that, or they are living in share houses well into their 30s (better to live in a shoebox in Bondi than be a homeowner in prole purgatory).

This downward mobility is causing millennial mids crippling status anxiety. Indeed, status anxiety has become the defining characteristic of this class. They live in constant fear of being perceived as proles, because they can no longer afford the lifestyle markers that once separated them from the working class.

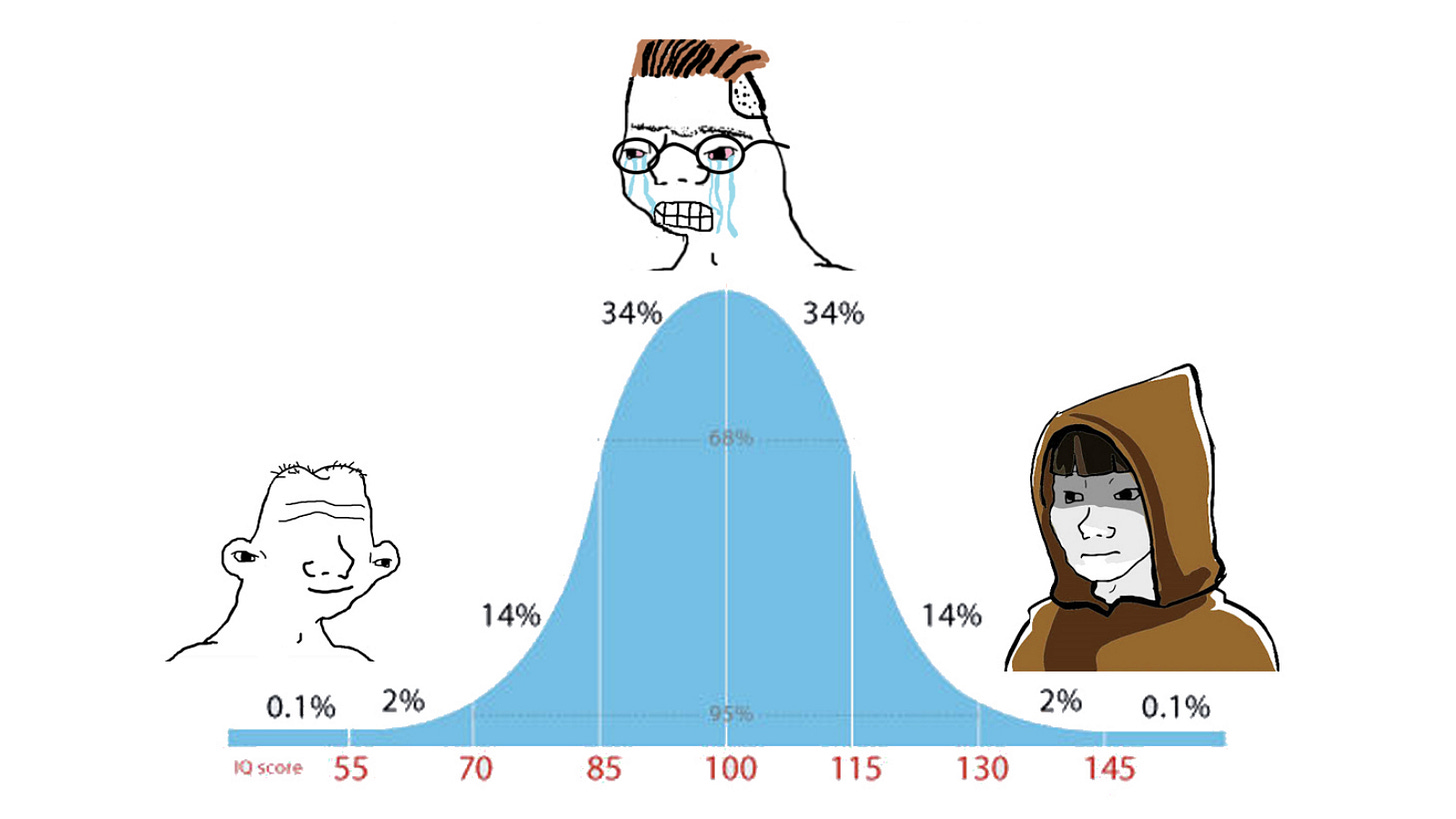

The mids try to compensate for their lack of economic capital by imitating UMC tastes, politics, and manners. But this imitation is often clumsy and ham-fisted, because the mids are mid-wits.

Mid-wits possess above average intelligence. Unlike the proles, they make an effort to ‘stay informed’. Occasionally, they even read a book. And of course, they went to university! All this leaves them with the erroneous impression that they are smart. But in reality, they’re just a standard deviation above the norm.

Because their intelligence isn’t immediately apparent, they’re forced to conspicuously signal their (rather limited) educational and cultural capital. This results in performative displays that lack symbolic complexity. For example, the mid-wit reads Mark Fisher’s ‘Capitalist Realism’ on the train (or better still, at a bar). They say ‘raison d’être’ instead of ‘reason’, and insist on being called ‘Dr’, even though their dissertation was on ‘Mindfulness in Middle School Mathematics’, or some shit.

Suffice to say, this need to prove intelligence signals its absence. Real intelligence, like old money wealth, doesn’t need to announce itself.

Mids tend to parrot the luxury beliefs of the upper–middle class. They talk about things like ‘white privilege,’ oblivious to the irony that they themselves aren’t particularly privileged.

Unlike the UMC, the mids aren’t economically insulated from the consequences of their luxury beliefs. The middle class girlboss, for example, will girlboss too hard to be marriageable, but not hard enough to actually be successful. She ends up as a childless thirty-something, clinging to a middle-management post in a government bureaucracy.

Luxury beliefs, like luxury goods, are subject to Prole Drift. Middle class emulation has severely reduced their cachet. As

If you tracked the average parental income of women with blue hair, it probably peaked around 2007, when it was associated with above average ‘privileged’ parents, and now it has crashed to the point where women with blue hair are decidedly part of the underclass. No luxury left in that signal.

Proles

We are frequently exhorted to sympathise with the struggles of the working class. Browse any bookshop and you will find sob stories about the ‘left behind’, such as Hillbilly Elegy, What’s the Matter with Kansas?, and Bowling Alone. Frankly, I’m sick of all this simpering. And if I’m being completely honest, I don’t pity the proles. The prole suffers physically, but he’s a free man when he isn’t working. The middle class office worker is never free, except when he’s dead.

The mids are expected to be inoffensive and characterless. Virtually no latitude is permitted to individuality or even the milder forms of eccentricity. The proles, by contrast, can say and think what they like. This is perhaps best demonstrated by their choice of bumper stickers. Drive past any building site in Australia, and you’ll see utes adorned with ‘Mud Slut,’ ‘CUNT,’ and ‘PatrolHub’ (styled after the Pornhub logo). Suffice to say, if a mid adorned their Subaru Forester with such stickers, they’d quickly be contacted by HR.

Furthermore, the proles aren’t expected to use corporate gobbledygook. When someone wastes their time, they can say ‘I’m not here to fuck spiders’, instead of ‘let’s prioritize activities that align with our core objectives.’ When someone makes a mistake, they get called a fucking idiot, instead of receiving a passive-aggressive email about ‘opportunities for improvement.’ And perhaps best of all, they don’t need to live in constant fear of saying something ‘culturally unsafe.’ They are free to think and say what they like. Why are the proles granted this freedom? I think George Orwell provided the answer in 1984.

In 1984, the Party makes no attempt to indoctrinate the proles. This is because they do not fear them. To quote Orwell:

What opinions the proles hold, or do not hold, is looked on as a matter of indifference. They can be granted intellectual liberty because they have no intellect. In a Party member, on the other hand, not even the smallest deviation of opinion on the most unimportant subject can be tolerated.

In addition to enjoying greater liberty of speech and thought, the proles get to pursue more enjoyable hobbies. Jet-skiing, fishing, hunting and four-wheel driving are all prole-coded activities. They’re also objectively fun. Meanwhile, the mids must pretend to enjoy yoga classes, mindfulness workshops, and hiking. While the mid trudges up a mountain trail in his Kathmandu gear, he can’t help but envy the Prole in his ‘Mud Slut’, effortlessly conquering terrain that will take him hours to walk.

The easiest way to identify a Prole is by looking at their driveway. There will be a boat on a trailer, dirt bikes under a tarp, and a car elevated on concrete blocks.The car is on concrete blocks because it is going to be repaired and restored. Which brings us to an important point about prole culture: among proles, status comes from practical skills. Being able to weld steel, operate heavy machinery, and rebuild an engine codes as high-status. The mid who calls roadside assistance for a flat tire would be considered low-status.

Lumpen-Proles

Karl Marx coined the term lumpenproletariat. He used it to describe the ‘social scum’ of society: criminals, vagabonds, beggars, and the chronically unemployed. Lumpen-proles do not earn their money. They rely on welfare, petty crime, or some combination of both.

Lumpen-proles are concentrated in dangerous social ecologies, such as housing commissions, ‘the projects’, or some other form of state-subsidized housing. Violence is common in such environments, so it is important for lumpen-proles to constantly signal their willingness to engage in it. Indeed, in these environments, there is a reversion to the most basic status hierarchy: physical dominance.

Physical dominance is the fundamental organizing principle of virtually all animal hierarchies. Male deer clash antlers during rutting season, with the victor claiming territory and mates. Silverback gorillas pound their chests to establish dominance within their troops. Male lions battle rivals to control prides and mating rights.

Human societies operated this way for millennia. Physical dominance determined access to resources and mates. Most of us now play more subtle status games, but lumpen-proles still follow these ancient rules. The youths of Chicongo adopt similar status-signaling strategies to the Mbuti of the Congo Basin. Jewelry becomes chains, war paint becomes tattoos, the spear becomes the Glock, but the underlying message remains the same: Me strong. Me kill you. Suffice to say, this is a signal with low symbolic complexity.

Interestingly, lumpen-proles appear to be the only class with above replacement levels of fertility. To quote

Workless households have the highest number of children per household, mixed households are in the middle, and households where both parents are working have the lowest average number of children per household. So-called ‘troubled’ or ‘problem’ households have even more children than workless households. Only the problem, workless, or partly workless households are reproducing at above replacement level.

In the past, high status and fertility were positively correlated. Only the wealthiest could afford to have large families. Large families were, therefore, upper-class coded. Today, high status and fertility are negatively correlated. Why is this?

argues ‘that in a modern liberal paradigm, having children provides a lower status payoff than competing pursuits.’ In other words, women prioritise career advancement, travel experience, and educational achievement, because these confer more status than motherhood.Kurtz convincingly argues that the fertility crisis can be explained by status. Or rather, lack of status. Being a stay-at-home Mum is increasingly seen as embarrassingly low-status. Even if one finds this analysis unconvincing, it is difficult to deny the immense influence that status dynamics exert over our decision making.

Conclusion

Please forgive me, dear reader. This gentle introduction to status has not been so gentle. It has been longwinded, persnickety, and--perhaps worst of all--thoroughly middle class. The unnecessary Latin etymology (‘statum’), the affected turns of phrase (‘suffice to say,’ ‘dear reader’), and the overwrought literary references all scream ‘look how educated I am.’ But as we have already established, a truly educated person whispers, rather than shouts.

Furthermore, information can’t serve as a strong signaling cost when information ‘wants to be free.’ Artificial intelligence and the democratisation of knowledge have made conspicuous erudition as gauche (a word I would probably mispronounce) as conspicuous consumption.

It is, therefore, necessary for mids to rethink their signalling strategy. In the next instalment of this series, I will outline some strategies for increasing your status as a downwardly mobile middle class or UMC man.

I think the spectrum of "status security" from low to high is a key defining factor between old money and new money and UMCs and down.

True old money aristocrats(perhaps 'aristocrats' in general) at least perceive themselves to be completely secure in their superior status, more or less on a spiritual level. A significant effect of this, is that it leads many of them to engage in activities, customs, dress, behavior etc without regard to how it is coded, or even in spite of its status-coding.

I feel click-baited.